Sent from my iPad

Begin forwarded message:

From: Kent Castle <kent.d.castle@hotmail.com>

Date: January 23, 2013 5:43:29 PM GMT-06:00

To: Martin Bobby <bobbygmartin1938@gmail.com>, Lee Alice <alicelee2009@gmail.com>, Lefebvre Gerry <glefebvre_houston1@comcast.net>, Leach Larry <ljleach@tds.net>, Chamberlain Sharon <sharon.m.chamberlain@saic.com>, Choban Peter <peter.s.choban@aero.org>, Tallman Curt <cgtallman@earthlink.net>

Subject: FW: Columbia's Final Flight

From: Subject: FW: Columbia's Final Flight

Date: Tue, 22 Jan 2013 21:21:13 -0600

'Just a Research Mission': Columbia's Final Flight (Part 1)

By Ben Evans

With less than six weeks remaining before the scheduled 16 January 2003 launch date, the STS-107 stack inches its way toward Pad 39A. Photo Credit: NASAEarly in the spring of 2001, the mission of STS-107 first sparked my interest, for two reasons. One was the fact that its seven-strong crew was relatively inexperienced—like that of Challenger, none had flown more than once in space—and the other was that it represented the first "stand-alone" scientific research flight performed by the shuttle for several years. With most of the missions around it devoted to International Space Station construction, Commander Rick Husband's flight seemed oddly out of place. "Why do you want to write about that one?" came the reply from the magazine Spaceflight, when I proposed an article on STS-107. "It's just a research mission?" Nonetheless, Spaceflight graciously supported my request to interview Husband and the article was published in October 2001. More than a decade later, I am glad that I took such an interest in STS-107, the final flight of Columbia and a mission which suddenly and drastically altered humankind's trajectory in space as few other missions have ever done, for better and for worse.

Rick Husband and I spoke for half an hour on the evening of 3 April 2001, over the telephone from his Houston office. I was in Liverpool, studying for my master's degree at the city's university, a couple of miles from the birthplace of Beatlemania. I could scarcely have imagined that Husband and his crew would be engulfed in the shuttle program's second disaster in less than two years' time, as they hypersonically knifed their way back through the atmosphere after an enormously successful 16-day flight. It is to my lasting regret that I never got the chance to tape record my conversation with Husband—only a page of hand-scribbled notes, later transferred onto a computer, exist as a memory—but I do recall the opening words of our exchange, when I realised I was talking one-to-one with a real, live astronaut. It is funny how certain things stand out about a person, and others do not, for my first impression was the depth of Husband's voice and his humor.When NASA PAO contacted me in March 2001 to agree to the interview and gave me a telephone number to call at a specific time on that day, I thought for an instant that someone was pulling my chain. Surely I wouldn't be connected directly to Husband's office … would I? I would certainly speak to his secretary or a PAO official in the first instance. I would be asked for my list of questions, such that Husband could be prepared in advance. As I dialed the number, I felt a twinge of excitement and nervousness. My hand-written notes and list of questions trembled in my hand.

Someone answered. Deep voice, Texan drawl. "Rick Husband."

Oh, hell, I thought, it's really him. Yet my stupidity still made me unsure.

"Good afternoon. Colonel Husband?"

"This is he."

"Colonel Husband, good afternoon. My name is Ben Evans and I'm … "

"Hi, Ben." As if he'd known me all my life. That set me at ease.

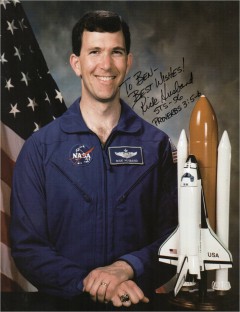

To start the interview, I reiterated thanks to him for a signed photograph that he had sent to me in late 1998, inscribed with the legend "Proverbs 3: 5-6." It seemed a logical place to start the interview and Husband seemed pleased that I had remembered the quote—Trust in the Lord with all your heart and lean not on your own understanding / In all your ways, submit to Him and He will make your paths straight—as he explained that "God's blessing and provision" had indeed guided his path since childhood, through engineering college, into the Air Force and test pilot school, into the hallowed ranks of NASA's astronaut corps, and into the exalted position of being selected to command the space shuttle. I stressed that he was the first pilot since Sid Gutierrez in April 1994 to lead a crew on only his second mission, but Husband brushed it off. Humbly, he said, it was nothing more than being in the right place at the right time.

Pictured at Ellington Field in front of one of NASA's T-38 training jets, the STS-107 crew—from left, Rick Husband, Willie McCool, Dave Brown, Laurel Clark, Ilan Ramon, Mike Anderson, and Kalpana Chawla—waited more than two years to launch. Photo Credit: NASAThere was, of course, much more to it than that. Kent Rominger—who commanded Husband's first mission and served as chief of the astronaut corps at the time of the STS-107 disaster and through the return to flight in mid-2005—later recalled that the selection had more to do with his expertise and skill in the cockpit. In her book High Calling, his widow, Evelyn, wrote of Rominger's recollection that Husband returned from his stint as pilot of STS-96 in June 1999, primed and ready for the commander's seat. "You really only need to know two things," reflected fellow astronaut Jim Halsell. "First, we recruited him into the astronaut office because of his wide-known reputation within the Air Force. Second, Rick was offered his own shuttle command after only one flight as a pilot, instead of the standard two. He was that good." Husband served a spell as chief of safety for the astronaut office, and in December 2000 was named to lead STS-107. Assigned alongside him was pilot Willie McCool, and the pair joined a previously announced quintet as multi-culturally diverse as they were multi-talented: an African-American (Mike Anderson), an Indian-American woman (Kalpana Chawla), two physicians (Dave Brown and Laurel Clark), and Israel's first spacefarer (Ilan Ramon). These five had been assigned in September 2000. They would support dozens of scientific experiments in the new Spacehab Research Double Module, housed in Columbia's payload bay, and a battery of instrumentation on the Freestar pallet.

From his earliest days watching the Mercury astronauts to private pilot's license to engineering college to Air Force test pilot and astronaut, Rick Husband trusted in the Lord with all his heart…and his path to the stars was truly rendered straight. Photo Credit: NASA/Ben Evans personal collectionLaunch was originally scheduled for August 2001, but was extensively postponed as NASA's oldest orbiter did not return to the Kennedy Space Center, after a $164 million program of modifications and upgrades, until early March of that year. According to Shuttle Program Manager Ron Dittemore, she was "a leaner, meaner machine," with more than 1,100 pounds of weight removed and wiring added to support an ISS-specification airlock and external docking adapter. Columbia had also been equipped to support the new Multifunction Electronic Display Subsystem (MEDS) "glass cockpit" to replace her outdated flight deck instrument suite. Despite these improvements, she remained too heavy to haul large ISS components in orbit and was committed at first to just two missions: STS-107 and the STS-109 Hubble Space Telescope servicing flight. The priority of the latter meant that it leapfrogged STS-107 and flew successfully in March 2002. Rick Husband's mission was tentatively rescheduled for July, some four months later.

Then, in mid-June, with barely five weeks to go, and with Columbia ready to roll over to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) for stacking onto her External Tank and twin Solid Rocket Boosters, a potentially show-stopping problem reared its head. Several cracks—each measuring around 0.09 inches in diameter—had turned up in metal liners, deep within the main engine plumbing of her sister ships, Discovery and Atlantis. Although the cracks did not hold pressure, and thus were not indicative of propellant leaks, it was feared that debris shed from them might work its way into an engine and possibly trigger an explosion. Repair work demanded the removal of Columbia's three engines and suspended preparations for STS-107 once again. Rick Husband took it in his stride. "We've had a fair number of slips through the course of our training," he told an interviewer in late June, "but we've made good use of those. This will be no different."

With emphasis placed upon the continued construction of the ISS, two other assembly missions—STS-112 and STS-113—flew ahead of Columbia, but by Christmas the STS-107 stack was "hard-down" on Pad 39A, tracking a 16 January 2003 launch. The liner cracks had been repaired, but another crack was found in a 2-inch metal bearing in one of Discovery's propellant line tie rod assemblies; this prompted another assessment and Columbia was cleared to fly. Like all of the post-9/11 shuttle missions, preparations were undertaken with intense security, with F-15 fighters and Army attack helicopters patrolling the KSC skies. The presence of Israeli Payload Specialist Ilan Ramon on the crew had served to ramp up this security level, with a tottering Middle East peace process and generally unstable political situation giving widespread concern. According to David Saleeba, a former Secret Service operative then working at the Cape as NASA's head of security, the space agency routinely monitored intelligence reports from the Department of Homeland Security, all of the armed forces, the FBI, Customs, and the FAA. Beach-front hotels occupied by high-ranking Israeli officials were subjected to random car stops and searches by armed officers and bomb-sniffing dogs. The astronauts' families all had police escorts. The departure times of the crew from Houston and their arrival in Florida were not publicly announced until the last minute, and the precise liftoff time was not revealed until shortly before launch.

Ilan Ramon, Laurel Clark and Mike Anderson participate in an ascent simulation. For Columbia's ill-fated re-entry, Clark would exchange places with Dave Brown on the flight deck. Photo Credit: NASA"I really don't enjoy launches," said Mike Anderson in a NASA interview. "Entries are a little bit better. It's a little quieter … not quite as violent. You can enjoy it a little bit. For me, on this flight's entry, I'm just going to sit down in my seat and hopefully reflect on the 16 days on-orbit that we've had, anxious to get back to Earth and give the scientists all their research results. I'll be happy to have the flight behind us."

The awesome challenge of bringing the crew together was Husband's responsibility. One of his methods was to take them on a team-building excursion, sponsored by the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), in August 2001. The seven of them backpacked into the mountains of Wyoming with a pair of NOLS instructors and spent nine nights and ten days with 60-pound packs in some of the toughest terrain in the United States. "We got to see some incredible scenery," recalled Husband. "We got to learn a lot about how each of us deal with the kind of situations that they put us into. It's also a challenge learning how to keep track of all your equipment, personally, then learning to work together … so that when you come back you know each other's strengths and weaknesses and so you can maximise that during the rest of your training flow." The trek took them through dense areas of the Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests—which featured treeless peaks in the 12,000-foot range—and high mountain lakes. Their guides, John Kanengieter and Andy Cline, led the expedition for the first few days, then the seven astronauts took turns to elect a new leader each day and evaluated each other's performance at nightfall. Despite the serious nature of the expedition, they treated it with aplomb and humor, even telephoning Houston from the 12,990-foot Wind River Peak to inform fellow astronauts that they had landed.

Yet the fact remained that this would be the least-experienced shuttle crew—in terms of space experience, that is—for several years. This made them the butt of several good-natured jokes, several of which they invented themselves. In April 2002, Jerry Ross had flown a record-breaking seventh mission, whereas the experienced members of STS-107 (Husband, Anderson, and Chawla) had barely three missions between them. "Before Jerry Ross flew his seventh mission," said Husband, "he had six flights to his credit. Our crew had only half that amount of flight experience … but after our flight we'll have caught up with him and then some!" Added Willie McCool, "He's got us beat by a factor of two, but when we come back we'll have ten flights among all of us and we'll jump ahead of Jerry."

Rick Husband, Willie McCool, and Dave Brown don training versions of their pumpkin-orange pressure suits, during a mission simulation. Photo Credit: NASAFor Ilan Ramon, it was peculiar to be the first Israeli in space. His mother was a Holocaust survivor from Auschwitz and his father had fought for the independence of Israel. During training, Ramon spoke to many other Holocaust survivors, and when he explained the nature of his mission they could only look at him with astonishment. To them, it was like a dream that they could have never dreamed was possible. The seed of the idea came in December 1995, when U.S. President Bill Clinton and Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres agreed "to proceed with space-based experiments in sustainable water use and environmental protection." As part of the deal, an Israeli astronaut would operate a multi-spectral camera to investigate the migration of airborne dust from the Sahara Desert and its impact upon global climatic change.

Ramon and the man who would later serve as his backup, Yitzhak May, were selected in April 1997 and began their official training the following year. The Mediterranean Israel Dust Experiment (MEIDEX) was a radiometric camera and wide-field-of-view video camera, mounted on a pallet at the rear of Columbia's payload bay and capable of operating across six spectral bands, from ultraviolet to infrared. Ramon also packed a pencil drawing, entitled "Moonscape," by Petr Ginz, a 14-year-old Czeckoslovakian Jew who died at Auschwitz in 1944. Ramon hoped that carrying it into space would symbolize "the winning spirit of this boy." Although he was a "secular" Jew, Ramon planned to take kosher food into orbit and hoped to observe the three Sabbaths that STS-107 would spend in space. As circumstances transpired, he would be so busy that he could only partly celebrate a single Sabbath.

Partly, that is, because that Sabbath was the final day of the mission, Saturday, 1 February 2003; a day which began with a bright and chirpy Ramon and his crewmates packing away their equipment for re-entry … and a day whose sun went down on one of the darkest days in U.S. and Israeli history.

Copyright © 2013 AmericaSpace - All Rights Reserved

===============================================================

AmericaSpace

For a nation that explores

January 20th, 2013

Working as a Team: Columbia's Final Flight (Part 2)

By Ben Evans

"We've had a Go for Auto Sequence Start. Columbia's on-board computers have primary control of all the vehicle's critical functions … "

More than two decades since her first flight, Columbia, the oldest orbiter in NASA's fleet of space shuttles, was ready for her 28th voyage on the morning of 16 January 2003. She would be carrying a crew of seven—Rick Husband, Willie McCool, Mike Anderson, Dave Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Laurel Clark, and Israeli payload specialist Ilan Ramon—into orbit for 16 days to perform dozens of scientific experiments in the Spacehab Research Double Module and aboard the Freestar pallet. The mission had been delayed for more than a year, due to difficulties endured during a lengthy process to upgrade Columbia, then cracked metal liners across the fleet in the summer of 2002. Now, at long last, STS-107 sat motionless on Pad 39A, attached to her bulbous External Tank and twin Solid Rocket Boosters, primed and ready to go. The astronauts had closed and locked their visors. A little more than two minutes ago, Willie McCool had reached over from the pilot's seat and activated Columbia's Auxiliary Power Units. Their ship now had hydraulic muscle.

"T-20 seconds and counting … "

Sitting in the commander's seat was Rick Douglas Husband, an Air Force colonel and veteran of one previous shuttle mission. Born in Amarillo, Texas, on 12 July 1957, he graduated from high school in his hometown, earned his private pilot's license, and entered Texas Tech University to study mechanical engineering. Since earliest childhood, Husband had been fascinated with the idea of someday becoming an astronaut, and his widow, Evelyn, in her book, High Calling, noted that he explained this to her at one of their first dates. Upon receipt of his degree in 1980, he entered the Air Force and underwent flight training at Vance Air Force Base in Oklahoma. Husband subsequently flew F-4 fighters and by the end of 1985 was serving as an instructor pilot and academic instructor at George Air Force Base in California. Two years later, his astronaut dream took another step forward when he was selected for the famed Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California, and upon graduation he flew the F-4 and all five versions of the F-15, working specifically on the latter's Pratt & Whitney F100-P2-229 increased performance engine. A master's degree followed and in mid-1992 Husband arrived at the Aircraft and Armament Evaluation Establishment at Boscombe Down, England, as an exchange pilot with the Royal Air Force, test flying several aircraft and serving as project pilot of the Tornado GR1 and GR4. Selected by NASA as an astronaut candidate in December 1994, he first flew as pilot on STS-96—the first International Space Station docking mission—in mid-1999.

" … 15 seconds … "

Rick Husband leads his crew out of the Operations & Checkout Building on the morning of 16 January 2003, bound for the Astrovan and Pad 39A. Photo Credit: NASASeated to Husband's right side on Columbia's flight deck was Navy commander William Cameron McCool, the pilot of STS-107. He came from San Diego, Calif., where he was born on 23 September 1961, the son of a Marine and naval aviator father. With such a background, it was always obvious that McCool would follow a naval career. After completing high school in Lubbock, Texas, he entered the Naval Academy and earned his degree in applied science in 1983, followed by a master's credential in computer science from the Naval Postgraduate School in 1985. After initial flight training, McCool was assigned to Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 129 at Whidbey Island, Wash., for the EA-6B Prowler. "The military and NASA are a lot alike when you talk about working together as a team," he said in a pre-flight interview. "We advocated crew co-ordination and working together as a crew. NASA does the same exact thing." During this period, he completed two overseas deployments aboard the USS Coral Sea to the Mediterranean region and was designated a wing-qualified landing signal officer. Selection for Naval Test Pilot School in Patuxent River, Md., followed shortly thereafter, and McCool's subsequent duties included working on airframe fatigue life studies, numerous avionic upgrades, and, of course, flight testing of the Prowler. He was an administrative officer aboard the USS Enterprise when he was selected by NASA in April 1996.

" … eleven, ten, nine, eight, seven … "

At ten seconds, a flurry of sparks swirled beneath the dark bells of Columbia's three engines, as hydrogen burn igniters fired to dissipate lingering quantities of the unburnt gas, ahead of Main Engine Start. The astronauts braced themselves for the immense push of engine ignition. Seated behind and between Rick Husband and Willie McCool was Kalpana Chawla, the flight engineer, who was making her second shuttle mission. Chawla had been the first Indian-American woman to be chosen for astronaut training in December 1994. She came from Karnal, in the state of Haryana, on 1 July 1961, and completed high school and received an aeronautical engineering degree from the Punjab Engineering College, before moving to the United States. Chawla earned her master's degree from the University of Texas in 1984 and a Ph.D. from the University of Colorado in 1988. Her NASA career began after receipt of her doctorate, and she spent several years working at the Ames Research Center on powered-lift computational fluid dynamics, simulating complex airflow around aircraft such as the Harrier. In 1993, she joined Overset Methods, Inc., working on a research team to implement techniques for aerodynamic optimization. In December of the following year, she was selected as an astronaut candidate. Her first flight was aboard STS-87 in late 1997. "Aircraft design," she said in one of her last interviews, "was really the thing I wanted to pursue. If people asked me what I wanted to do [in college], I would say 'I want to be a flight engineer.'" On STS-107, she would be just that, for the position of flight engineer on the Shuttle—working with Husband and McCool to continuously monitor hundreds of displays and instruments during the most dynamic phases of flight—was one of the most demanding roles of the whole crew.

Kalpana Chawla, the flight engineer on STS-107, pictured during an emergency bailout training exercise in November 2002. Photo Credit: NASA" … We have a Go for Main Engine Start … "

All at once, the four astronauts on the flight deck and their three comrades on the darkened middeck felt a huge rush and a gigantic outpouring of sheer power as turbopumps awoke, liquid oxygen and hydrogen flooded into the combustion chambers of Columbia's main engines, and they roared to life for what would be the final time. Such was their power that they actually shifted the orbiter slightly "upwards" on the External Tank struts, in a phenomenon known as "the twang," before settling ahead of the ignition of the twin Solid Rocket Boosters at T-zero. Seated shoulder-to-shoulder with Kalpana Chawla, and directly behind Willie McCool, the muscles of rookie astronaut David McDowell Brown tensed. The Navy captain and flight surgeon was making his first mission. Born in Arlington, Va., on 16 April 1956, Brown attended high school in his hometown and gained a degree in biology from the College of William and Mary and a medical doctorate from Eastern Virginia Medical School, then joined the Navy. He trained as a flight surgeon and in 1984 became the Director of Medical Services at the Navy Branch Hospital in Adak, Alaska. He subsequently deployed to the western Pacific aboard the USS Carl Vinson and in 1988 became the only flight surgeon for ten years to be selected for pilot training. "I pursued things that I was interested in," he said in one of his final interviews. "I don't think I was afraid of working hard and went down a path that I thought would be really challenging, and lo and behold, this is where it ended up!" Designated a Naval Aviator two years later (and ranking No. 1 in his class), Brown flew the A-6E aircraft, served as a Strike Leader Attack Training Syllabus Instructor and Contingency Cell Planning Officer, and qualified in the F-18. By 1995, the year before his selection by NASA, he was serving as flight surgeon at the Naval Test Pilot School in "Pax River," Md.

" … three, two, one … "

By now, the three blazing engines were at near-full power; their translucent orange plumes replaced by a trio of dancing Mach diamonds. If the four astronauts on Columbia's flight deck, with its six wrap-around front windows and two overhead windows, had a sense of seeing the enormity of the controlled explosion that was going on around them, their three crewmates on the middeck had no such luxury. They could rely only upon the feelings in their bodies and the sounds. Of those three, only payload commander Michael Phillip Anderson—Air Force lieutenant-colonel and physicist—had flown into space before. He was born on Christmas Day in 1959 in Plattsburgh, N.Y., the son of an Air Force pilot—"an Air Force brat," he once said—and grew up on Air Force bases around the United States. Anderson earned his degree in physics and astronomy from the University of Washington and a master's in physics from Creighton University. Betwixt his two degrees, he entered the Air Force and after training served as Chief of Communications Maintenance for the 2015 Communications Squadron and later Director of Information System Maintenance for the 1920 Information System Group. Flight training followed in 1986 and Anderson piloted the EC-135 for the Strategic Air Command. His later career carried him through roles as diverse as aircraft commander, instructor pilot, and tactics officer, before selection into NASA's astronaut corps in December 1994. Anderson made his first shuttle flight on STS-89 in January 1998.

" … We have booster ignition … "

Pictured during training in September 2001, Ilan Ramon was Israel's first astronaut. Photo Credit: NASAAt some stage in the milliseconds after 10:39 am EST on 16 January 2003, Space Shuttle Columbia's twin Solid Rocket Boosters—like a pair of colossal Roman candles, stacked on either side of the bulbous External Tank—spewed columns of golden flame and STS-107 took flight. For the last time, Columbia spread her wings under her own power. Hold-down bolts were explosively sheared and the behemoth began its climb for the heavens. Seated on the middeck, Ilan Ramon must have reflected in those adrenaline-charged seconds upon the importance of this mission for himself and for Israel. Born in Tel Aviv on 20 June 1954, Ramon entered the Israel Air Force Flight School and trained on the A-4, Mirage III-C, and F-16 aircraft. In 1981, he served as Deputy Squadron Commander B of the Israeli Air Force's F-16 Squadron. Ramon earned a degree in electronics and computer engineering from Tel Aviv University in 1987 and rose in his military career to become a Squadron Commander and Head of the Aircraft Branch in the Operations Requirement Department and, later, Head of the Department of Operational Requirement for Weapon Development and Acquisition. These posts ended in 1998, when Ramon began dedicated space shuttle training. "When I was selected," he told a NASA interviewer, "I really jumped, almost to space. I was very excited." As recounted in yesterday's history article, Ramon's mission marked a watershed moment for a nation and religion which had emerged from the trauma of Second World War persecution and, whether for good or ill, had asserted itself in the Middle East.

Scattering hordes of terrified seabirds, Columbia rockets into orbit for the final time on 16 January 2003. Never again would the whole vehicle be seen directly and up close by human eyes. Photo Credit: NASA" … and Liftoff of Space Shuttle Columbia with a multitude and national and international space research experiments … "

Next to Ramon was a second Navy flight surgeon, Captain Laurel Blair Salton Clark, also making her first space mission. Clark came from Ames, Iowa, where she was born on 10 March 1961, and studied zoology as an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then entered medical school and earned her doctorate in 1987. During this period, she undertook active-duty training with the Diving Medicine Department at the Naval Experimental Diving Unit and commenced Navy undersea medical officer training in 1989. Clark's naval career included numerous medical evacuations from U.S. submarines, and she became a qualified flight surgeon, deploying overseas to the western Pacific. She was serving as a flight surgeon for the Naval Flight Officer advanced training squadron in Pensacola, Fla., when she was selected by NASA in April 1996. "I never really thought about being an astronaut or working in space myself," she said before launch. "I was very interested in environment and ecosystems and animals." That changed over time with her developing naval and medical expertise. "It was really just sort of a natural progression when I learned about NASA," Clark added, "and what astronauts do and the type of things that they are expected to do, that I thought about the things I had done so far and became more interested in that as a career."

Video courtesy of NASA

Columbia rose from Earth to the cheers and Hebrew prayers of an assembled multitude. The picture-perfect launch would make headlines in Tel Aviv, providing a brief distraction from the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict. Even Tiewfiek Khateeb, an Arab-Israeli member of parliament, described it as "a happy occasion," but refused to be drawn on whether the goodwill might be extended into politics. Said Daniel Ayalon, Israel's ambassador to the United States: "Only two generations after the Jewish people were at their lowest ebb, on the very demise … here we are soaring up and making great achievements."

An adventurer and explorer at heart, Willie McCool was making his first space mission on STS-107. Photo Credit: NASA / Ben Evans personal collectionAs STS-107 cleared the Pad 39A launch tower and climbed into a beautifully clear Florida sky, Columbia kicked off an ambitious series of six shuttle missions planned for 2003 … and the only flight not destined for the International Space Station. In fact, not since 1998 had a long-duration shuttle mission been devoted exclusively to multidisciplinary experiments, and this caused concern to both the scientific community and Congress, who were keenly aware that the United States might lose its "lead" in the microgravity research arena. At a March 2000 hearing, Congressman Dana Rohrabacher had declared that "We can't expect the scientific community to remain engaged if researchers do not see hope that there will be research flight opportunities on a regular basis." Moreover, performing experiments for a couple of weeks offered a highly valuable testbed before committing them in the longer term to the ISS. At length, Spacehab, Inc., which had been building pressurised science modules since the 1980s, offered its new Research Double Module to support 80 investigations. To Mike Anderson, responsible for overseeing the integration of payload requirements into an effective timeline that he and his crew could follow, it was clear from the enormous breadth and depth of STS-107's experiments that this mission was one that the scientists had waited a long time to see happen. The workload would be great, but the payoffs were expected to be equally so.

As Columbia vanished from view in the sky, heading for orbit, no one could possibly have foreseen the calamity that would ungulf her, two weeks hence. No one could have guessed that she would never be seen up close by human eyes again. No one could have guessed that the STS-107 crew would never hold their loved ones again. And no one could have imagined that Columbia would accomplish 99.9 percent of her mission and fight like a trooper to save her human occupants and bring them safely home. A tough 16 days lay ahead … and beyond that lay an even tougher two and a half years.

Copyright © 2013 AmericaSpace - All Rights Reserved

===============================================================

No comments:

Post a Comment